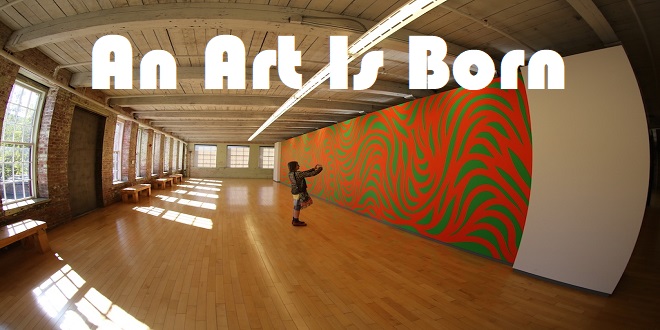

An Art Is Born

The Laugh-Makers

As the comedy team strives to find a common denominator, their lines sound more scripted. Verbal content is the essence of stand-up comedy. Other stocking-trade aspects of legitimate theatre – notably costumes, scenery, and make-up – are avoided or considered minor. Although stand-up comedy was initially presented only to live audiences, later it became available over the radio and still later on television and long-playing records. Most recently, comics have been selling their humor on videotape.

The preceding might be considered a narrow scientific definition, which we shall refer to as pure stand-up comedy. However, in show business and everyday life, the art is less precisely defined. For example, some male comics blithely define themselves as entertainers who “grab their crotch” while on stage. Since show business usage bears on this study in many ways, let us establish here and now some terminological distinctions that will help bridge the gap between the vocabularies of science and entertainment.

Precursor s

To be verbally humorous, on or off the stage, requires a certain mastery of language and movement. In addition, the comic’s verbal and theatrical expression must be unique, unlike the expression of ordinary people when they talk about the same things. Otherwise, the presentation would be too routine and lacking in humor. Verbal comedy also requires exceptional language ability and a receptive audience, one that sees the comedian’s conception and oral presentation as ludicrous.

Phase 1: the beginning

According to the broad definition of show business, if one person were singled out as the first stand-up comic, it would have to be Mark Twain. For approximately fifty years, starting in 1856 with an after-dinner speech, he toured the United States as a “humorous lecturer.” In this role, he delivered monologues of various lengths on numerous subjects, many of which were treated with wit and satire. Twain would lounge onstage, drawling out tall tales and anecdotes, pausing skilfully while his audience roared with laughter at specific passages. He had, for those days, a unique lecturing style.

Phase 2: the concert act

Vaudeville, usually staged in large theatres and civic auditoriums, faded from the scene in the early 1930s. This coincided with the rise of two new venues for stand-up comedy and other acts: nightclubs and the “Borscht Belt” of Catskill Mountains resort hotels near New York City. These places did not offer variety shows. Instead, a comic or some other single performer would present an entire show, possibly all the shows, on a given evening. They explained what today’s cartoons call a concert and sometimes did so for several successive nights.

Phase 3: amateur experimentation

Younger, less established performers had little interest in becoming “line comics.” The times were changing. These “new wave” comics (Playboy 1961) wanted to develop their material in more extended and connected units. America was beset with political tension from the late 1950s to the early 1970s – the life-span of new wave comedy. The public mind was forced to consider such issues as official corruption, racial inequality, police violence, and foreign war. All forms of humor that addressed these subjects were timely. To be sure, they were sometimes discussed with one-liners, but the monologue, often satirical, enabled a more thorough examination. This was the approach of Lenny Bruce and Mort Sahl, among the few comics of their type, to achieve professional status in this era.

The Rise of the Professional

Two significant factors helped change the stand-up comic’s financial situation. One was the comics’ strike in 1979 in Los Angeles and the threat of another that same year in New York. The details are presented by Burns, and her conclusion is of interest here: “Many credits the strike with being one of the most important elements in creating the current comedy ‘boom’ because, although the [new] payments were modest, they produced a significant result: comics could now, with a full week’s worth of sets, afford to support themselves by doing comedy.” Moreover, now there were amateurs and professionals in stand-up comedy who could be distinguished by the act’s level of pay and quality.

Summary

It appears that this chronology represents the mere beginnings of the art of stand-up comedy. Rogers, but without resurrecting their lengthy monologues. The transition brought something new to entertainment: take-home humor. Most live variety comedy is lost once presented. We can only watch and appreciate the antics of the clown, the juggler’s skills, and the magician’s tricks. We cannot replay for our friends the gestures of the talented mime or the intricate details of a lengthy monologue. Of course, one-liners, street jokes, and ethnic gags could be taken home, but by the early 1960s, the last was increasingly considered racist, and the first two were simply commonplace. By contrast, the descriptive monologues and narrative jokes of the modern comic fit the bill perfectly; they were then, as they are now, of manageable length and about familiar events, delivered in a conversational style that invited repeating the next day at work, at the bar, in the den, whatever.